Getting people to church was not enough to reveal all that God was and is doing in and through people's lives. The north American church was busy but just not very good at making disciples, a mark of a Biblically-defined missional congregation. As suggested previously, what really counts may not be counting individuals at a particular time each week. It might be better to take cues from the past, namely Wesley's "societies," and count smaller and more intimate gatherings of active believers, what I call "circles."

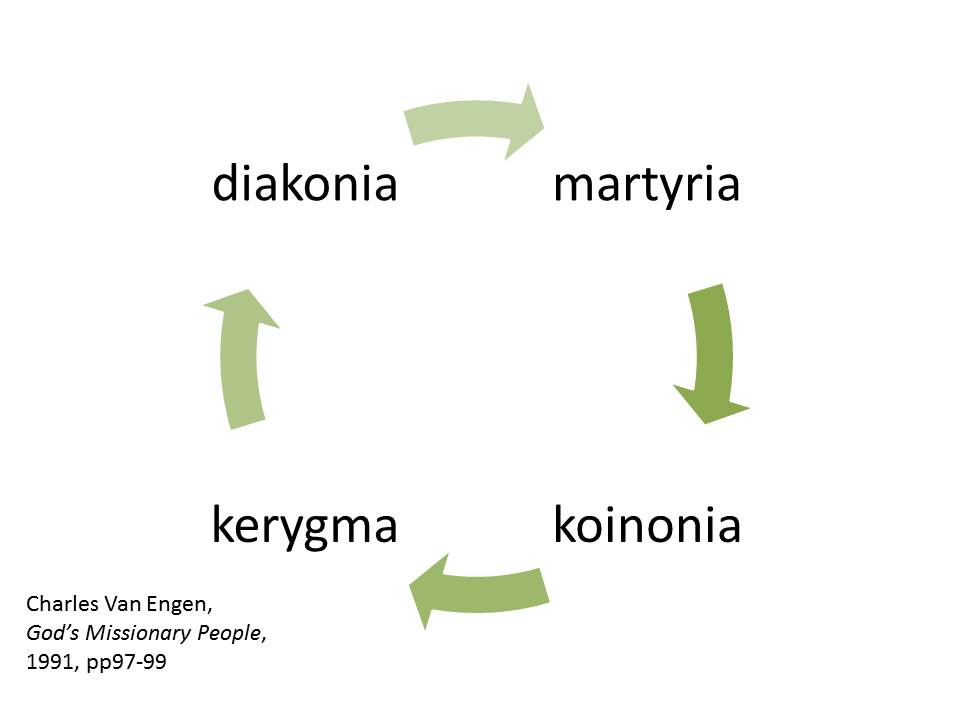

It may not be necessary for each group of believers to emphasize all four purposes equally, but they should have at least one of the purposes as a primary motivation. The fourfold missional purpose of the church activated by gathered circles of believers could become tangible means of evaluating the total missional impact of the church. For example, take the following hypothetical situation of Generic First Church. This fellowship of believers holds two Sunday morning worship services, ten discipleship classes every Sunday morning between services, nine home groups on Sunday evening and some others throughout the week, four service teams that volunteer three days a week across the city, three foreign mission teams that gather for prayer and training for two-week trips throughout the year, two worship teams that gather for prayer and practice during the week and on Sundays prior to worship, pastoral staff gathers once a week for planning, eight informal groups of men and women gathering for accountability and fellowship, children’s and youth groups meeting in various formats weekly and monthly, and a launch team readying for a new church plant in a neighboring community. Yet the main category of effective ministry currently implemented by the church and recorded by the overseeing district is how many individuals attended the Sunday morning worship services. In many ways, in light of all the church is called to do, the Sunday morning attendance count misses the mark in measuring the total missional impact of the church. Only one or two circles are counted. What if the number of circles, i.e. groups and teams mentioned above, were categorized by their intentional purpose (witness, fellowship, proclamation, service) and counted as the reflection of the church’s total missional impact in the world? What if the value of a church was not that it is “running 325 on Sunday mornings” but rather taking the Sunday morning worship service as a single local church gathering along with affirming the other forty-two total circles being sent into the world creating real missional impact by envisioning the purposes of the church, making disciples, and multiplying outwardly? The only difficulty rests in how to categorize each circle by how much it reflects one or more of the four intentional tasks of the church.

In the end, the purpose and task of the circle communicates what really matters in the church in its total missional impact. It could be adapted to every expression of the church from the home group to the local church to the district to conferences to regional associations. Counting circles reveals the total capacity of the Church to fulfill its intentional purposes through its missional calling in the world and becomes the central concern of evaluating what it is and what it does in making an impact in its neighborhood. This is the fifth installment in blog series on Evaluating the Missional Impact of the Church: Part 1 - What Really Counts? Part 2 - Nickels & Noses Part 3 - On a Mission from God Part 4 - Counting What Really Matters

0 Comments

The search for what really counts in church has been a personal journey. Prior to leaving for West Africa in 2002, I found several insights from the book Linked: The New Science of Networks by Albert-László Barabàsi. Since then it was recently reprinted. This work provides the mental scaffolding for dealing with complex relationships and the rapid growth of networks. While serving in West Africa, a Mennonite colleague shared another book that a supporter had sent to him by Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom. It became a centerpiece of weekly conversations among my little circle of missionary colleagues from four countries and six denominations. The spider and the starfish continued to be primary metaphors for reflection on the missionary work in which I was involved. An informal curriculum for multiplying churches began to unfurl through a growing list of reflective practitioners associated with a more organic, networked approach to multiplying churches, such as Roland Allen, David Garrison, Neil Cole, Michael Frost, and Alan Hirsch. Several of their works are found in my current course syllabi for ministry and intercultural studies majors at Mount Vernon Nazarene University where I now teach. In the mid-2000s, this crash course of new thinking was perfectly timed to an explosion of rapid multiplication in the church in Benin, my place of service at the time. The rapid change dramatically and radically transformed what was most important in evaluating the work of a church in the local context. The over-emphasis on who shows up when was replaced by how many groups have begun this week and where. I spent more time trying to facilitate the training of ministers than crunch numbers for local church. I spent more time developing materials in simple English and French so the material could be quickly translated into the dozens of local languages for discipling new converts. I focused most of my attention on the work of a team of four leaders instead of micro-managing every facet of this explosive growth which became much bigger than anything I'd yet encountered. It can be said that I was schooled in an Book of Acts approach to being the Church--miracles almost too fantastic to be true but too real to dismiss easily, powerful and large-scale response to simple tellings of the Gospel, traumatic and continual crises inside and outside the church, consistent testimony to the work of the Holy Spirit against all odds in the human realm. Recent engagement with organic church network leaders and district leaders within the Church of the Nazarene, especially through the Nazarene Organic Church Network, have now culminated in my thinking about a new way of evaluating the missional impact of the local church in a given context. Instead of counting individual adherents, members or attendees, the church should begin counting circles. But, first things first.

Each of these tasks take place in the midst of the church’s regular process of gathering and scattering (cf. Acts 2:42-47). Seldom does a Christian believer venture completely alone into the world. These disciples are sent by fellow co-workers, are joined by them, or are covered in prayer by them. The in-gathering of the church also provides the place for increasing the capability and capacity for continual witness and service. Continual feeding needs an outlet for pent-up spiritual energy, so also the people's witness and service must spiral outward into the surrounding community.  The fellowship, however, is never broken though it may be multiplied. The gospel is heard together, experienced, validated, and sent with each believer as they fulfill each purpose of the gathered church by scattering outwardly. Visually, these actions can be depicted as a spiraling circle, such as that found in the triskelion found in the prehistoric ruins at Newgrange, Ireland, and later used in one of the high points of Celtic art depicted in the monastic Book of Kells. So, why should the church continue to count individual participants as the sole means of evaluating church when it barely gets to the heart of the church’s total missional impact? Individual believers cannot send themselves, go by themselves or last very long on their own. They are only sent as communal participants, cognizant of their connection to the community. Wouldn’t it be better to count the intimate circle, the gathered and sacramental body, to which the believer belongs and from which he or she is sent into the world? Does this not reflect the intentional tasks to which the disciple, and thus the church, is called to be and do, to become and to accomplish? If so, what circles in the fellowship of believers should then be counted? These questions will be the focus of the next installment of evaluating the missional impact of the church. Next, Circles of Missional Impact, Part 5 in blog series on Evaluating the Missional Impact of the Church: Part 1 - What Really Counts? / Part 2 - Nickels & Noses / Part 3 - On a Mission from God

Local churches cannot rely solely on asking who is there every Sunday to proof its importance. We can't just say "we're on a mission from God" and hope everyone else accepts our version of who we are. There has to be another way to identify the working out of God’s purposes in a church. Attempts have been made in recent years to find organizational purpose through the creation of mission statements. Patrick Hull at Forbes.com offers the following four questions to help small businesses (and churches) identify their missions:

Churches have followed the business world, used similar questions, and created written platforms about their common purpose and activities. A familiar example of a local church mission statement is found at Saddleback Community Church in Orange County, California. Their mission statement is "to provide a place where depressed, the hurting, and hopeless can come and find help. To be a place of family, community, and hope” by incorporating the P.E.A.C.E plan to plant churches that promote reconciliation, equip servant leaders, assist the poor, care for the sick, and educate the next generation. Each new member follows a four-track process of recognizing this purpose individually through becoming a member, moving into maturity, finding a ministry, and entering into mission in the local context, usually identified as moving around a baseball diamond.

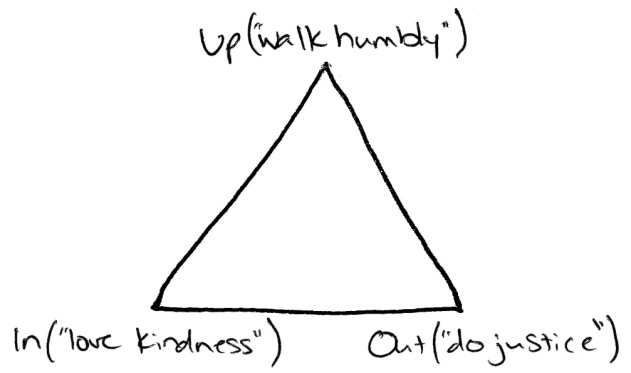

Micah 6:8 to characterizes the purpose of Christian life together as UP-IN-OUT. According to John P. Chandler of the SpenceNetwork.net, it can mean something like this:

"'Walk humbly' – our relationship Up toward God, who desires from us passionate spirituality. 'Love kindness' – our relationships In toward others we know and love, demonstrated in radical community; and 'Do justice' – our relationship Out to the world, characterized by a missionary zeal"

A denominational application of stating organizational purpose through a mission statement is found in the Church of the Nazarene: “To make Christ-like disciples in the nations.” This mission statement flows from the core values of being Christian, Holiness and Missional.[4] In each of these examples, the mission statements can be tested biblically and can be contextually expressed without diluting the purpose. The resulting purpose can now be used to evaluate how well members, local churches, associated groups like districts, publications, educators, and mission teams are accomplishing the organization’s purpose.

Theologically, the Church has a task in that it is sent by God into the world for His purposes. The question remains: how is this mission evaluated? There needs to be an objective, a target, before any activity can be evaluated. The missio Dei, gathered from the words of missiologist David Bosch, is the “privileged participation” of the church as it obediently strives to join God in his self-revelation to the world (Transforming Mission, 2011, p. 10). God is already present and at work in the most isolated and alienated places on earth. The task of the disciple is simply to join God where He already is. Jesus was the first one initiated into the incarnational task followed by those believing in Him. The words of Jesus speak of this missional purpose: “As you [the Father] sent me into the world,” Jesus said. “I have sent them.” (John 17:18 NIV). These words of Jesus are bracketed in verses 17 and 19 by the proclamation of the powerful work of God in forming those who are sent out. “Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth . . . For them I sanctify myself, that they too may be truly sanctified.” (NIV) The disciples as Christ’s body in the world become a holy offering, set apart by God for His work, and in many ways become the sacramental presence of Christ. This then is the missional calling of the church: To be very God’s presence in the world and carry out His work there. Therefore, the Church cannot be content to tabulate attendance numbers to evaluate its impact within the larger community. There is a need to count what really matters. There is something to be said for a biblically based, contextually-centered mission statement. Of course, this is only a first step in identifying “what really matters.” The second step is to decide exactly what to count. Next, Counting What Really Matters, Part 4 in blog series on Evaluating the Missional Impact of the Church: Part 1 - What Really Counts? & Part 2 - Nickels & Noses "Nickels and noses" euphemistically refers to the number of people attending a worship service and the amount of money received in the offering plate. A local pastor once admitted that local churches tend to value the ABCs: "Attendance, Buildings, and Cash.” This way of talking about what counts, especially attendance numbers, has also been highlighted in the 2010 Religious Membership and Congregations Study conducted by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies.

Furthermore, the data can be used for comparisons between religious groups as well as comparing affiliated and unclaimed populations in a particular geographic area. These data are a good starting point in order to discover religious identities in certain locations of the United States. But several questions are begging to be asked. How are these individual adherents tracked in teh transient society found in north America? What of the numerous non-denominational Christian churches emerging in the last few decades? What if people do not identify themselves as belonging to the Christian churches that they most identify with spiritually?

The preponderance of "soul liberty" remains a central tenet within the American psyche since the Baptist Roger Williams left the Puritan-governed Massachusetts Bay Colony to found the religiously open colony of Rhode Island. What happens when persons considered themselves Christian but do not affiliate with any religious group? What if someone considers himself or herself part of a church but the church does not? The numerical data is something but not everything. True, the numbers tell a story. There is a narrative behind every number. The numbers begin to answer some questions but also give rise to many more. Returning to the original question from Part 1: What really counts in church? What do these numbers show about not only who is present in a community but also what the churches and its members do as part of a community? What is there to say about the relative importance and intentionality of their activities within the context of the larger community? It could be these numbers only tell us who is attracted to particular churches and religious groups in certain areas but not much about what happens once they get there. Next, "On a Mission from God": What Really Counts?, Part 3 What “counts” is an English colloquialism for noting what activities and events matter and how to evaluate intentional participation in these activities. For example, the “Monthly Stats” page of a district website in the Church of the Nazarene offers fields for pastors to include average attendance numbers for Sunday School, Morning Worship, and Responsibility List. This is not an attempt to belittle this district, which itself acknowledges the dubious nature of the task in reference to the quote about statistics and lies, often attributed to Mark Twain and many others. The district asks churches to report what is expected by the denomination.

This is no surprise to worship service attendees perusing worship bulletin inserts distributed by district offices every quarter showing average Sunday School and worship attendance numbers for all of the local organized churches listed by zones or mission areas. Sometimes, a column is given that shows how these numbers have increased or decreased from the previous installment. At the end of the church year, the District Assembly gathers these numbers into a district journal offering proof of who was in church on Sundays. Nazarenes are not alone in giving value to attendance numbers. We are also not immune to the deep scars these numbers may cause. A few years ago, Methodist Robert Linthicum, a three-decade veteran of urban ministry, lamented that the process of gathering attendance numbers for the small church pastor. “I know of no instrument created by our denomination that gives city pastors a greater sense of failure and of little worth than this annual book of statistics… driving home to the city pastor how ‘little’ he or she has accomplished…the previous year.”[1] This commentary on counting attendance was published over twenty years ago. Over the next two decades, little has changed in the value denominations still attribute to attendance numbers. Next Sunday, ushers will continue to collect the offering and take account of who is where in the church building during Sunday morning worship services. From the hard-to-believe-if-it-didn’t-happen-to-me file, there is a local church in a city not to be named that had created a peep hole in the flat stone wall behind the pulpit to allow the church secretary to have a direct view of every pew and in order to count who was really there. Most church leaders are expected to track attendance in small groups, midweek activities, worship services, and fellowship events from the local church to the district auxiliaries. Just a few weeks ago, a big deal was made in a nearby local church about the number of teenagers participating in an all-night youth lock-in in which students went sledding, played basketball and video games, and consumed large amounts of caffeine. It makes one wonder about the significance of this accounting and if it truly holds churches accountable to its primary purpose and mission in the world: To make Christlike disciples in the nations. So, what really counts in church? Coming Soon: Part 2--Nickels and Noses [1] Robert Linthicum, City of God, City of Satan: A Biblical Theology of the Urban Context (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991), 292. |

Bio

teacher, writer, Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed