|

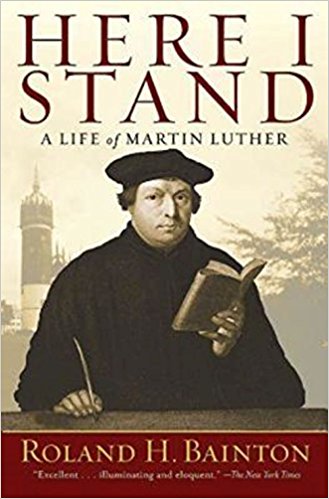

Here is a list of books I use as required reading regularly in my courses at Mount Vernon Nazarene University. Merry Christmas!

There are 27 books representing eleven courses. There are 32 authors. Only four are women. Five are non-white or persons of color.

I might be doing some curriculum revision so I wanted to see all at once what my required reading list looks like.

0 Comments

"Such a view [of the priesthood of all believers] was fraught with far-reaching consequences for the theory of the Church, and Luther's own view of the Church was derivative from his theory of the sacraments. His deductions, however, were not clear-cut in this area, because his view of the Lord's Supper pointed in one direction and his view of baptism in another. That is why he could be at once to a degree the father of the congregationalism [p141] of the Anabaptists and of the territorial church of the later Lutherans. "His view of the Lord's Supper made for the gathered church of convinced believers only, because he declared that the sacrament depends for its efficacy upon the faith of the recipient. That must of necessity make it highly individual because faith is individual. Every soul, insisted Luther, stands in naked confrontation before its Maker. No one can die in the place of another; everyone must wrestle with the pangs of death for himself alone. 'Then I shall not be with you, nor you with me. Everyone must answer for himself.' Similarly, 'The mass is a divine promise which can help no one, be applied for no one, intercede for no one, and be communicated to none save him only who believes with a faith of his own. Who can accept or apply for another the promise of God which requires faith of each individually?' "Here we are introduced to the very core of Luther's individualism. It is not the individualism of the Renaissance, seeking the fulfillment of the individual's capacities; it is not the individualism of the late scholastics, who on metaphysical grounds declared that reality consists only of individuals, and that aggregates like Church and state are not entities but simply the sum of their components. Luther was not concerned to philosophize about the structure of Church and state; his insistence was simply that every man must answer for himself to God. That was the extent of his individualism. The faith requisite for the sacrament must be one's own. From such a theory the obvious inference is that the Church should consist only of those possessed of a warm personal faith; and since the number of such persons is never large, the Church would have to be a comparatively small conventicle. Luther not infrequently spoke precisely as if this were his meaning. Especially in his earlier lectures he had delineated a view of the Church as a remnant because the elect are few. This must be so, he held, because the Word of God goes counter to all the desires of the natural man, abasing pride, crushing arrogance, and leaving all human pretensions in dust and ashes. Such a work is unpalatable, and few will receive it. Those who do will be stones rejected by the builders. Derision and persecution will be their lot. Every Abel is bound to have [p142] his Cain, and every Christ his Caiaphas. Therefore the true Church will be despised and rejected of men and will lie hidden in the midst of the world. These words of Luther might readily issue in the substitution for the Catholic monastery of the segregated Protestant community. "But Luther was not willing to take this road because the sacrament of baptism pointed for him in another direction. He could readily enough have accommodated baptism to the preceding view, had he been willing, like the Anabaptists, to regard baptism as the outward sign of an inner experience of regeneration appropriate only to adults and not to infants. But this he would not do. Luther stood with the Catholic Church on the score of infant baptism because children must be snatched at birth from the power of Satan. But what then becomes of his formula that the efficacy of the sacrament depends upon the faith of the recipient? He strove hard to retain it by the figment of an implicit faith in the baby comparable to the faith of a man in sleep. But again Luther would shift from the faith of the child to the faith of the sponsor by which the infant is undergirded. Birth for him was not so isolated as death. One cannot die for another, but one can in a sense be initiated for another into a Christian community. For that reason baptism rather than the Lord's Supper is the sacrament which links the Church to society. It is the sociological sacrament. For the medieval community every child outside the ghetto was by birth a citizen and by baptism a Christian. Regardless of personal conviction the same persons constituted the state and the Church. An alliance of the two institutions was thus natural. Here was a basis for a Christian society. The greatness and the tragedy of Luther was that he could never relinquish either the individualism of the eucharistic cup or the corporateness of the baptismal font. He would have been a troubled spirit in a tranquil age." (Chapter VIII, The Wild Boar in the Vineyard, pp. 140-142)

"General dissemination was not in Luther's mind when he posted the theses. He meant them for those concerned. A copy was sent to Albert of Mainz along with the following letter: 'Father in Christ and Most Illustrious Prince, forgive me that I, the scum of the earth, should dare to approach Your Sublimity. The Lord Jesus is my witness that I am well aware of my insignificance and my unworthiness. I make so bold because of the office of fidelity which I owe to Your Paternity. May Your Highness look upon this speck of dust and hear my plea for clemency from you and from the pope.' "Luther then reports what he had heard about Tetzel's preaching that through indulgences men are promised remission, not only of penalty but also of guilt. "'God on high, is this the way the souls entrusted to your care are prepared for death? It is high time that you looked into this matter. I can be silent no longer. In fear and trembling we must work out our salvation. Indulgences can offer no security but only the remission of external canonical penalties. Works of piety and charity are infinitely better than indulgences. Christ did not command the preaching of indulgences but of the gospel, and what a horror it is, what a peril to a bishop, if he never gives the gospel to his people except along with the racket of indulgences. In the instructions of Your Paternity to the indulgence sellers, issued without your knowledge and consent [Luther offers him [p.85] a way out], indulgences are called the inestimable gift of God for the reconciliation of man to God and the emptying of purgatory. Contrition is declared to be unnecessary. What shall I do, Illustrious Prince, if not to beseech Your Paternity through Jesus Christ our Lord to suppress utterly these instructions lest someone arise to confute this book and to bring Your Illustrious Sublimity into obloquy, which I dread but fear if something is not done speedily? May Your Paternity accept my faithful admonition. I, too, am one of your sheep. May the Lord Jesus guard you forever. Amen.' "WITTENBERG, 1517, on the eve of All Saints "'If you will look over my theses, you will see how dubious is the doctrine of indulgences, which is so confidently proclaimed.' "MARTIN LUTHER, Augustinian Doctor of Theology'" "[Cardinal] Albert [of Brandenburg and Victor of Mainz 1514-1545] forwarded the theses to Rome. Pope Leo is credited with two comments. In all likelihood neither is authentic, yet each is revealing. The first was this: 'Luther is a drunken German. He will feel different when he is sober.' And the second: 'Friar Martin is a brilliant chap. The whole row is due to the envy of the monks.' "Both comments, wherever they originated, contain a measure of truth. If Luther was not a drunken German who would feel different when sober, he was an irate German who might be amenable if mollified. If at once the pope had issued the bull of a year later, clearly defining the doctrine of indulgences and correcting the most glaring abuses, Luther might have subsided. On many points he was not yet fully persuaded in his own mind, and he was prompted by no itch for controversy. Repeatedly he was ready to withdraw if his opponents would abandon the fray. During the four years while his case was pending his letters reveal surprisingly little preoccupation with the public dispute. He was engrossed in his duties as a professor and a parish priest, and much more concerned to find a suitable incumbent for the chair of Hebrew at the University of Wittenberg than to knock a layer from the papal tiara." (Chapter V, The Son of Inquity, pp. 84-85)

"'Indulgences are most pernicious because they induce complacency and thereby imperil salvation. Those persons are damned who think that letters of indulgence make them certain of salvation. God works by contraries so that a man feels himself to be lost in the very moment when he is on the point of being saved. When God is about to justify a man, he damns him. Whom he would make alive he must first kill. God's favor is so communicated in the form of wrath that it seems farthest when it is at hand. Man must first cry out that there is no health in him. He must be consumed with horror. This is the pain of purgatory. I do not [p83] know where it is located, but I do know that it can be experienced in this life. I know a man who has gone through such pains that had they lasted for one tenth of an hour he would have been reduced to ashes. In this disturbance salvation begins. When a man believes himself to be utterly lost, light breaks. Peace comes in the word of Christ through faith. He who does not have this is lost even though he be absolved a million times by the pope, and he who does have it may not wish to be released from purgatory, for true contrition seeks penalty. Christians should be encouraged to bear the cross. He who is baptized into Christ must be as a sheep for the slaughter. The merits of Christ are vastly more potent when they bring crosses than when they bring remissions."" (Quotation from the 95 Theses, Chapter IV, The Onslaught, pp. 82-83)

"Indulgences are positively harmful to the recipient because they impede salvation by diverting charity and inducing a false sense of security. Christians should be taught that he who gives to the poor is better than he who receives a pardon. He who spends his money for indulgences instead of relieving want receives not the indulgence of the pope but the indignation of God. We are told that money should be given by preference to the poor only in the case of extreme necessity. I suppose we are not to clothe the naked and visit the sick. What is extreme necessity? Why, I ask, does natural humanity have such goodness that it gives itself freely and does not calculate necessity but is rather solicitous that there should not be any necessity? And will the charity of God, which is incomparably kinder, do none of these things? Did Christ say, 'Let him that has a cloak sell it and buy an indulgence'? Love covers a multitude of sins and is better than all the pardons of Jerusalem and Rome." (Quotation from the 95 Theses. Chapter IV, The Onslaught, p. 82, boldfaced added)

'"Most serious of all was Luther's reduction of the mass to the Lord's Supper. The mass is central for the entire Roman Catholic system because the mass is believed to be a repetition of the Incarnation and the Crucifixion. When the bread and wine are transubstantiated, God again becomes flesh and Christ again dies upon the altar. This wonder can be performed only by priests empowered through ordination. Inasmuch as this means of grace is administered exclusively by their hands, they occupy a unique place within the Church; and because the Church is the custodian of the body of Christ, she occupies a unique place in society. "Luther did not attack the mass in order to undermine the priests. His concerns were always primarily religious and only incidentally ecclesiastical or sociological. His first insistence was that the sacrament [p139] of the mass must be not magical but mystical, not the performance of a rite but the experience of a presence. This point was one of several discussed with Cajetan at the interview. The cardinal complained of Luther's view that the efficacy of the sacrament depends upon the faith of the recipient. The teaching of the Church is that the sacraments cannot be impaired by any human weakness, be it the unworthiness of the performer or the indifference of the receiver. The sacrament operates by virtue of a power within itself ex opere operato. In Luther's eyes such a view made the sacrament mechanical and magical. He, too, had no mind to subject it to human frailty and would not concede that he had done so by positing the necessity of faith, since faith is itself a gift of God, but this faith is given by God when, where, and to whom he will and even without the sacrament is efficacious; whereas the reverse is not true, that the sacrament is of efficacy without faith. 'I may be wrong on indulgences,' declared Luther, 'but as to the need for faith in the sacraments I will die before I will recant.' This insistence upon faith diminished the role of the priest who may place a wafer in the mouth but cannot engender faith in the heart. "The second point made by Luther was that the priest is not in a position to do that which the Church claims in the celebration of the mass. He does not 'make God,' and he does not 'sacrifice Christ.' The simplest way of negating this view would have been to say that God is not present and Christ is not sacrificed, but Luther was ready to affirm only the latter. Christ is not sacrificed because his sacrifice was made once and for all upon the cross, but God is present in the elements because Christ, being God, declared, 'This is my body.' The repetition of these words by the priest, however, does not transform the bread and wine into the body and blood of God, as the Catholic Church holds. The view called transubstantiation was that the elements retain their accidents of shape, taste, color, and so on, but lose their substance, for which is substituted the substance of God. Luther rejected this position less on rational than on biblical grounds. Both Erasmus and Melanchthon before him had pointed out that the concept of substance is not biblical but a scholastic sophistication. [p.140] For that reason Luther was averse to its use at all, and his own view should not be called consubstantiation. The sacrament for him was not a chunk of God fallen like a meteorite from heaven. God does not need to fall from heaven because he is everywhere present throughout his creation as a sustaining and animating force, and Christ as God is likewise universal, but his presence is hid from human eyes. For that reason God has chosen to declare himself unto mankind at three loci of revelation. The first is Christ, in whom the Word was made flesh. The second is Scripture, where the Word uttered is recorded. The third is the sacrament, in which the Word is manifest in food and drink. The sacrament does not conjure up God as the witch of Endor but reveals him where he is." (Chapter VIII, The Wild Boar in the Vineyard, pp. 139-140)

"Luther's Ninety-Five Theses ranged all the way from the complaints of aggrieved Germans to the cries of a wrestler in the night watches. One portion demanded financial relief, the other called for the crucifixion of the self. The masses could grasp the first. Only a few elect spirits would ever comprehend the full import of the second, and yet in the second lay all the power to create a popular revolution. Complaints of financial extortion had been voiced for over a century without visible effect. Men were stirred to deeds only by one who regarded indulgences not merely as venal but as blasphemy against the holiness and mercy of God. "Luther took no steps to spread his theses among the people. He was merely inviting scholars to dispute and dignitaries to define, but others surreptitiously translated the theses into German and gave them to the press. In short order they became the talk of Germany. What Karl Barth said of his own unexpected emergence as a reformer could be said equally of Luther, that he was like a man climbing in the darkness a winding staircase in the steeple of an ancient cathedral. In the blackness he reached out to steady himself, and his hand laid hold of a rope. He was startled to hear the clanging of a bell." (Chapter IV, The Onslaught, p. 83)

"During the summer of 1520 he delivered to the printer a sheaf of tracts which are still often referred to as his primary works: The Sermon on Good Works in May, The Papacy at Rome in June, and The Address to the German Nobility in August, The Babylonian Captivity in September, and The Freedom of the Christian Man in November. [p137] The latter three pertain more immediately to the controversy and will alone engage us for the moment. "The most radical of them all in the eyes of contemporaries was the one dealing with the sacraments, entitled The Babylonian Captivity, with reference to the enslavement of the sacraments by the Church. This assault on Catholic teaching was more devastating than anything that had preceded; and when Erasmus read the tract, he ejaculated, 'The breach is irreparable.' The reason was that the pretensions of the Roman Catholic Church rest so completely upon the sacraments as the exclusive channels of grace and upon the prerogatives of the clergy, by whom the sacraments are exclusively administered. If sacramentalism is undercut, then sacerdotalism is bound to fall. Luther with one stroke reduced the number of the sacraments from seven to two. Confirmation, marriage, ordination, penance, and extreme unction were eliminated. The Lord's Supper and baptism alone remained. The principle which dictated this reduction was that a sacrament must have been directly instituted by Christ and must be distinctively Christian. "The removal of confirmation and extreme unction was not of tremendous import save that it diminished the control of the Church over youth and death. The elimination of penance was much more serious because this is the rite of the forgiveness of sins. Luther in this instance did not abolish it utterly. Of the three ingredients of penance he recognized of course the need for contrition and looked upon confession as useful, provided it was not institutionalized. The drastic point was with regard to absolution, which he said is only a declaration by man of what God has decreed in heaven and not a ratification by God of what man has ruled on earth." (Chapter VIII, Wild Boar in the Vineyard, pp. 136-137, boldface added) To be continued . . .

"[I]ndulgences served not merely to dispense the merits of the saints but also to raise revenues. They were the bingo of the sixteenth century. The practice grew out of the crusades. At first indulgences were conferred on those who sacrificed or risked their lives in fighting against the infidel, and then were extended to those who, unable to go to the Holy Land, made contributions to the enterprise. The device proved so lucrative that it was speedily extended to cover the construction of churches, monasteries, and hospitals. The gothic cathedrals were financed in this way. Frederick the Wise was using an indulgence to reconstruct a bridge across the Elbe. Indulgences, to be sure, had not degenerated into sheer mercenariness. Conscientious preachers sought to evoke a sense of sin, and presumably only those genuinely concerned made the purchases. Nevertheless, the Church today readily concedes that the indulgence traffic was a scandal, so much so that a contemporary preacher phrased the requisites as three: contrition, confession, and contribution." (Chapter IV, Onslaught, p. 72)

In response to those that would make haste of the reformation and turn it into an "occasion of division, war, and insurrection," Luther wrote, "'Give men time. I took three years of constant study, reflection, and discussion to arrive where I now am, and can the common man, untutored in such matters, be expected to move the same distance in three months? Do not suppose that abuses are eliminated by destroying the object which is abused. Men can go wrong with wine and women. Shall we then prohibit wine and abolish women? The sun, the moon, and stars have been worshiped. Shall we then pluck them out of the sky? Such haste and violence betray a lack of confidence in God. See how much he has been able to accomplish through me, though I did no more than pray and preach. The Word did it all. Had I wished I might have started a conflagration at Worms. But while I sat still and drank beer with Philip and Amsdorf, God dealt the papacy a mighty blow.'" (Chapter XII, The Return of the Exile, p. 214)

|

Bio

teacher, writer, Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed