|

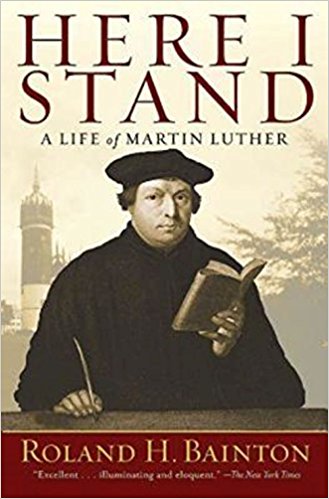

"Such a view [of the priesthood of all believers] was fraught with far-reaching consequences for the theory of the Church, and Luther's own view of the Church was derivative from his theory of the sacraments. His deductions, however, were not clear-cut in this area, because his view of the Lord's Supper pointed in one direction and his view of baptism in another. That is why he could be at once to a degree the father of the congregationalism [p141] of the Anabaptists and of the territorial church of the later Lutherans. "His view of the Lord's Supper made for the gathered church of convinced believers only, because he declared that the sacrament depends for its efficacy upon the faith of the recipient. That must of necessity make it highly individual because faith is individual. Every soul, insisted Luther, stands in naked confrontation before its Maker. No one can die in the place of another; everyone must wrestle with the pangs of death for himself alone. 'Then I shall not be with you, nor you with me. Everyone must answer for himself.' Similarly, 'The mass is a divine promise which can help no one, be applied for no one, intercede for no one, and be communicated to none save him only who believes with a faith of his own. Who can accept or apply for another the promise of God which requires faith of each individually?' "Here we are introduced to the very core of Luther's individualism. It is not the individualism of the Renaissance, seeking the fulfillment of the individual's capacities; it is not the individualism of the late scholastics, who on metaphysical grounds declared that reality consists only of individuals, and that aggregates like Church and state are not entities but simply the sum of their components. Luther was not concerned to philosophize about the structure of Church and state; his insistence was simply that every man must answer for himself to God. That was the extent of his individualism. The faith requisite for the sacrament must be one's own. From such a theory the obvious inference is that the Church should consist only of those possessed of a warm personal faith; and since the number of such persons is never large, the Church would have to be a comparatively small conventicle. Luther not infrequently spoke precisely as if this were his meaning. Especially in his earlier lectures he had delineated a view of the Church as a remnant because the elect are few. This must be so, he held, because the Word of God goes counter to all the desires of the natural man, abasing pride, crushing arrogance, and leaving all human pretensions in dust and ashes. Such a work is unpalatable, and few will receive it. Those who do will be stones rejected by the builders. Derision and persecution will be their lot. Every Abel is bound to have [p142] his Cain, and every Christ his Caiaphas. Therefore the true Church will be despised and rejected of men and will lie hidden in the midst of the world. These words of Luther might readily issue in the substitution for the Catholic monastery of the segregated Protestant community. "But Luther was not willing to take this road because the sacrament of baptism pointed for him in another direction. He could readily enough have accommodated baptism to the preceding view, had he been willing, like the Anabaptists, to regard baptism as the outward sign of an inner experience of regeneration appropriate only to adults and not to infants. But this he would not do. Luther stood with the Catholic Church on the score of infant baptism because children must be snatched at birth from the power of Satan. But what then becomes of his formula that the efficacy of the sacrament depends upon the faith of the recipient? He strove hard to retain it by the figment of an implicit faith in the baby comparable to the faith of a man in sleep. But again Luther would shift from the faith of the child to the faith of the sponsor by which the infant is undergirded. Birth for him was not so isolated as death. One cannot die for another, but one can in a sense be initiated for another into a Christian community. For that reason baptism rather than the Lord's Supper is the sacrament which links the Church to society. It is the sociological sacrament. For the medieval community every child outside the ghetto was by birth a citizen and by baptism a Christian. Regardless of personal conviction the same persons constituted the state and the Church. An alliance of the two institutions was thus natural. Here was a basis for a Christian society. The greatness and the tragedy of Luther was that he could never relinquish either the individualism of the eucharistic cup or the corporateness of the baptismal font. He would have been a troubled spirit in a tranquil age." (Chapter VIII, The Wild Boar in the Vineyard, pp. 140-142)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Bio

teacher, writer, Archives

August 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed